A newborn’s vision is mostly blurry, but the visual system develops over time and is fully formed in the teen years. Learn how to protect your child’s vision with regular eye screenings as they grow.

Recommended Schedule for Child Vision Screenings

A vision screening is a more efficient eye exam. A child is “screened” for eye problems and referred to an ophthalmologist for a comprehensive exam if needed.

Your child’s vision can be screened by a:

Pediatrician

Family physician

Ophthalmologist

or other properly trained health care provider

Screenings are also offered at schools, community health centers or community events.

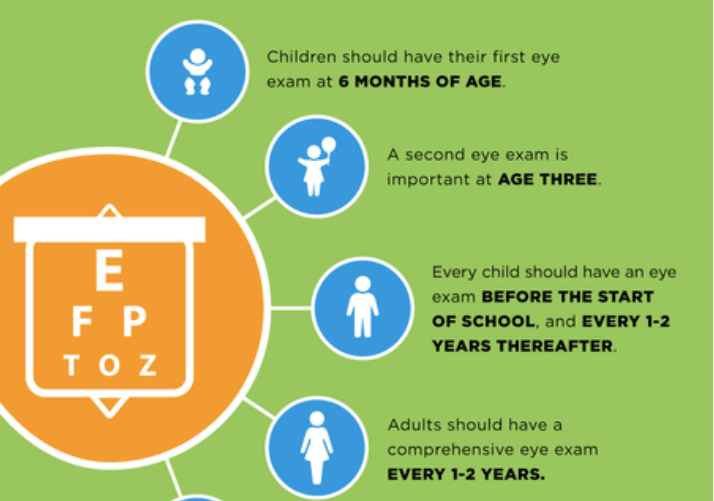

The American Academy of Ophthalmology and the Strabismus & Pediatric Ophthalmology Society of India recommend the following schedule:

Newborn

A doctor or other trained health professional should examine a newborn’s eyes to check for basic indicators of eye health. It may include testing for:

a “red reflex” (like seeing red eyes in a flash photograph). If the bright light shone in each eye does not return a red reflex, more testing may be needed.

blink and pupil response

An ophthalmologist does a comprehensive exam if the baby is:

born prematurely

has signs of eye disease

or a family history of childhood eye disease

6 to 12 months

A second screening should be done during the child’s first year of life. This screening is usually done at a well-child exam between 6 and 12 months. Your child’s pediatrician or other health care professional should:

do the tests mentioned above

visually inspect the eyes

check for healthy eye alignment and movement

12 to 36 months

Between 12 and 36 months, a child is checked for healthy eye development. There may be a “photoscreening” test. A special camera takes pictures of your child’s eyes. These pictures help find problems that can lead to amblyopia (lazy eye). If they see a problem, your child may be referred to an ophthalmologist.

3 to 5 years

Between 3 and 5 years, a child’s vision and eye alignment should be checked. This may be done by a pediatrician, family doctor, ophthalmologist, optometrist, or orthoptist.

Visual acuity (sharpness of vision, like 20/20 or 6/6 for example) should be tested as soon as the child is old enough to read an eye chart. Many children are somewhat farsighted (hyperopic), but can also see clearly even at distance. Most children will not require glasses or other vision correction. If the child struggles with the eye chart, photo screening may be used to test vision.

An ophthalmologist should see your child if the screening shows signs of:

misaligned eyes (strabismus)

“lazy eye” (amblyopia)

refractive errors (myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism)

or another focusing problem

Begin treatment for these problems as soon as possible—getting early treatment for your child is the best thing you can do to protect their vision.

5 years and older

At 5, children should be screened for visual acuity and alignment. Nearsightedness (myopia) is the most common problem in this age group. It is corrected with eyeglasses. An ophthalmologist should examine a child with misaligned eyes or signs of other eye problems. Children treated with growth hormone therapy should have their eyes tested before and during treatment.

What’s the difference between a vision screening and a comprehensive eye exam?

A comprehensive eye exam diagnoses eye disease. Eye drops are used to dilate (widen) the pupil during the exam. This gives your ophthalmologist a fuller view inside the eyes. With dilation and other special testing, signs of eye disease are more evident. It is a good practice for the parents to seek a comprehensive eye exam if:

their child fails a vision screening

vision screening is inconclusive or cannot be done

referred by a pediatrician or school teacher/nurse

their child has a vision complaint or observed abnormal visual behavior, or is at risk for developing eye problems. Children with medical conditions (such as Down syndrome, prematurity, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, neurofibromatosis) or a family history of amblyopia, strabismus, retinoblastoma, congenital cataracts, or glaucoma are at higher risk for developing pediatric eye problems.

their child has a learning disability, developmental delay, neuropsychological condition, or behavioral issue.